Hands on with PostgreSQL transactions

- 6 minsLife would have been a lot easier without concurrency or parallelism.

Everything working sequentially. Cars moving one by one on a single lane road, no overtaking, no accidents. Sounds simple and straightforward.

But it is a tradeoff, because:

- all cars need to run at a constant speed.

- if one stops in between, the road is chocked.

- a limited number of cars can pass in/out at any given point of time.

This is not feasible at present with current requirement where target is to increase the number of cars passing in/out (high throughput) and decrease travel time (low latency). This can be easily solved with the help of lanes.

Similarly in technical terms, let’s say your API takes 1s, then in 24hrs, you can only serve 86,400 (24 * 60 * 60) requests. Thus serving in sequential fasion is not an option when you are building for current generation, with 640,000 daily active internet users.

So you need to handle requests concurrently/parallelly. At the server level, this can be easily achieved with the help of threads (or equivalent). But how will you handle this at the database layer?

This boils down to a simple money transaction problem. Which is, two API calls are initiated simultaneously, to transfer 50 bucks from A to B. Both the calls are running parallelly in different threads, both read the balance of A as 60 bucks and validates the checks and performs transaction. Eventually leading to undesired output.

One simple way to solve this is to queue requests and execute one by one. This will drastically impact your throughput. On a second thought, why you want to block another person from transferring money when A and B are transacting, at this same point C can transfer to D or vice versa without causing any problem.

So you want to execute requests concurrently/parallelly but those requests should not belong to the same person.

Here comes the database transactions in the picture.

Note: The scope of this blog is only limited to PostgreSQL transactions.

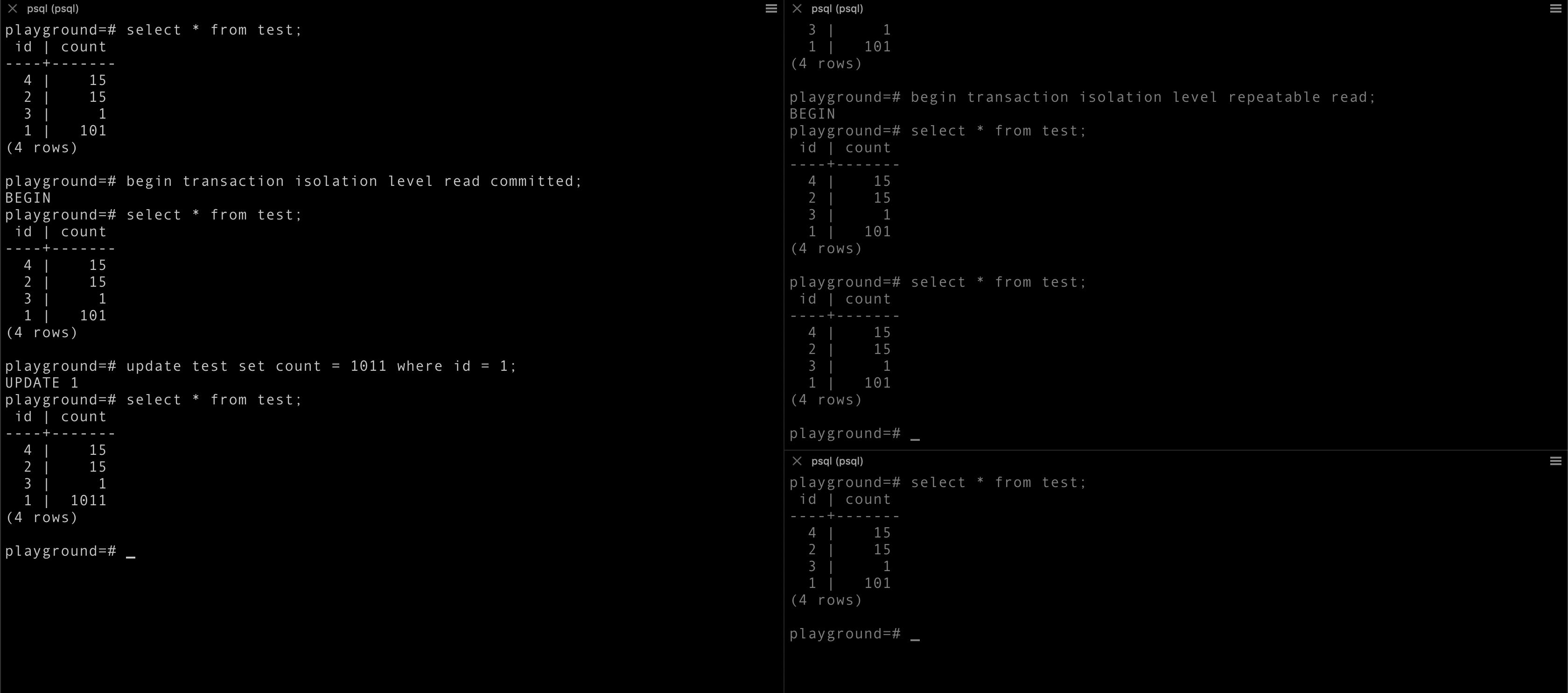

Postgresql transactions

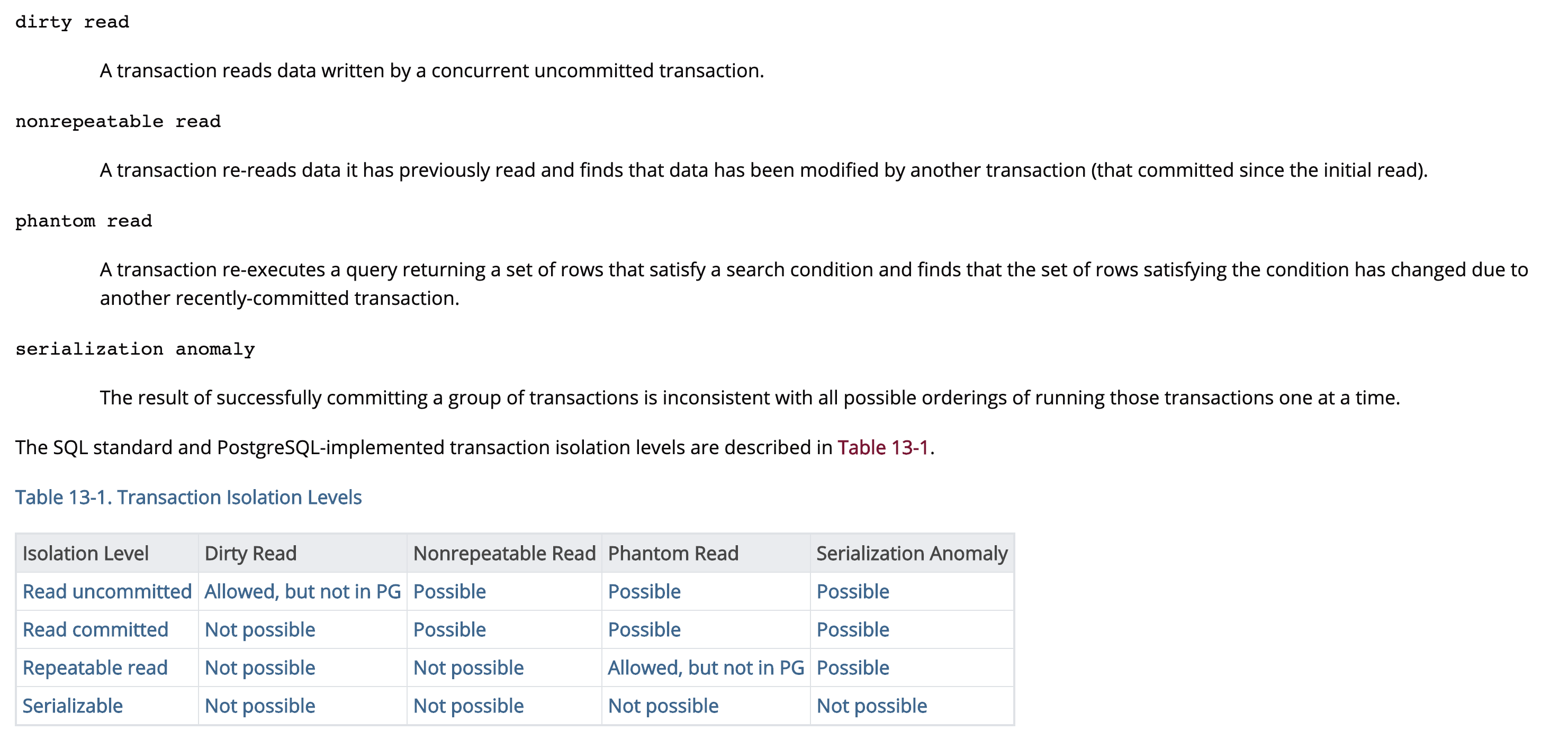

Basically, there can be 4 situations: dirty read, nonrepeatable read, phantom read and serialization anomaly, which can lead to data corruption:

And to handle all these 4 scenarios, there can be four types of isolation level.

Thanks to PostgreSQL, that it automatically takes care of Dirty Read, i.e you won’t be able to read any uncommitted change by another concurrent transaction.

Let’s go through each isolation level one by one.

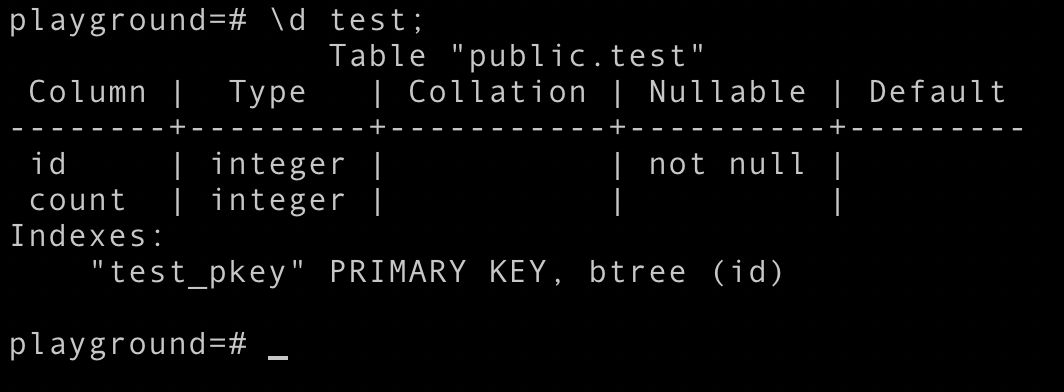

Note: In this whole blog, I will be taking example with the help of relation whose schema looks like this:

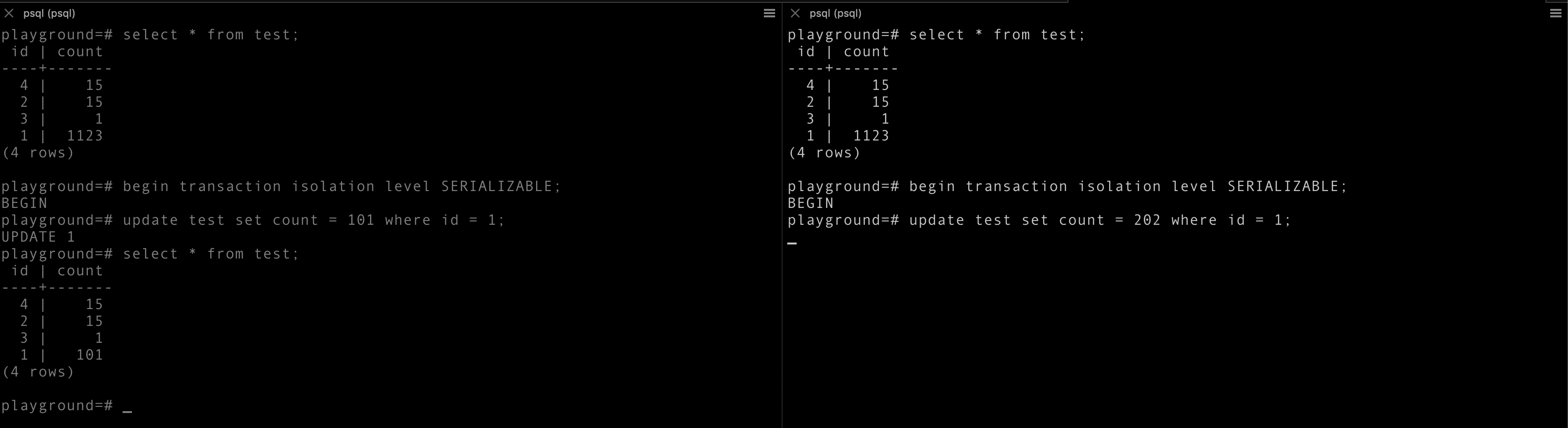

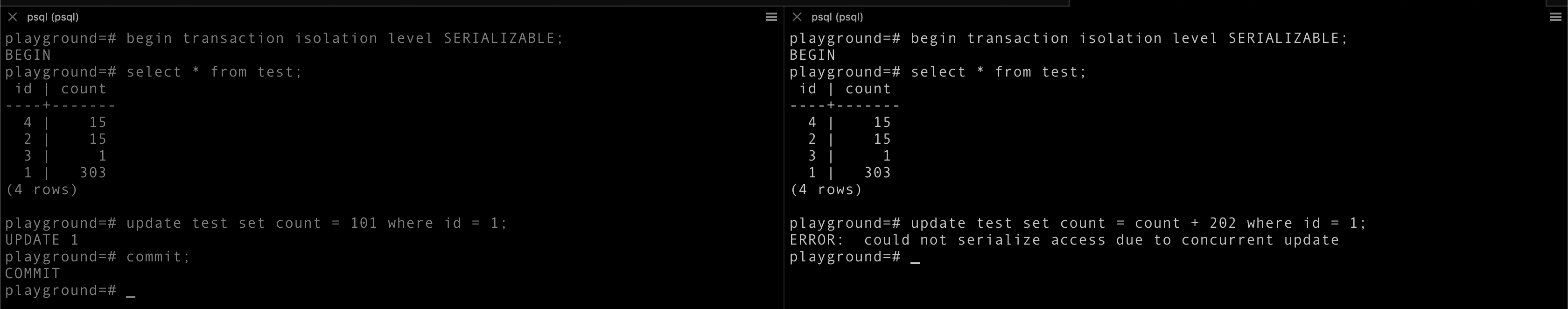

Serializable transaction

This is one of the simplest isolation level. Exactly similar to what we have discussed above, cars running in a single lane.

Or in other words, one transaction is allowed at a time.

As you can see, the later (right side) transaction is waiting for the first (left side) transaction to either commit or rollback.

- Let’s see what happens if we commit left-hand side transaction, then right-hand one failed with the error:

ERROR: could not serialize access due to concurrent update

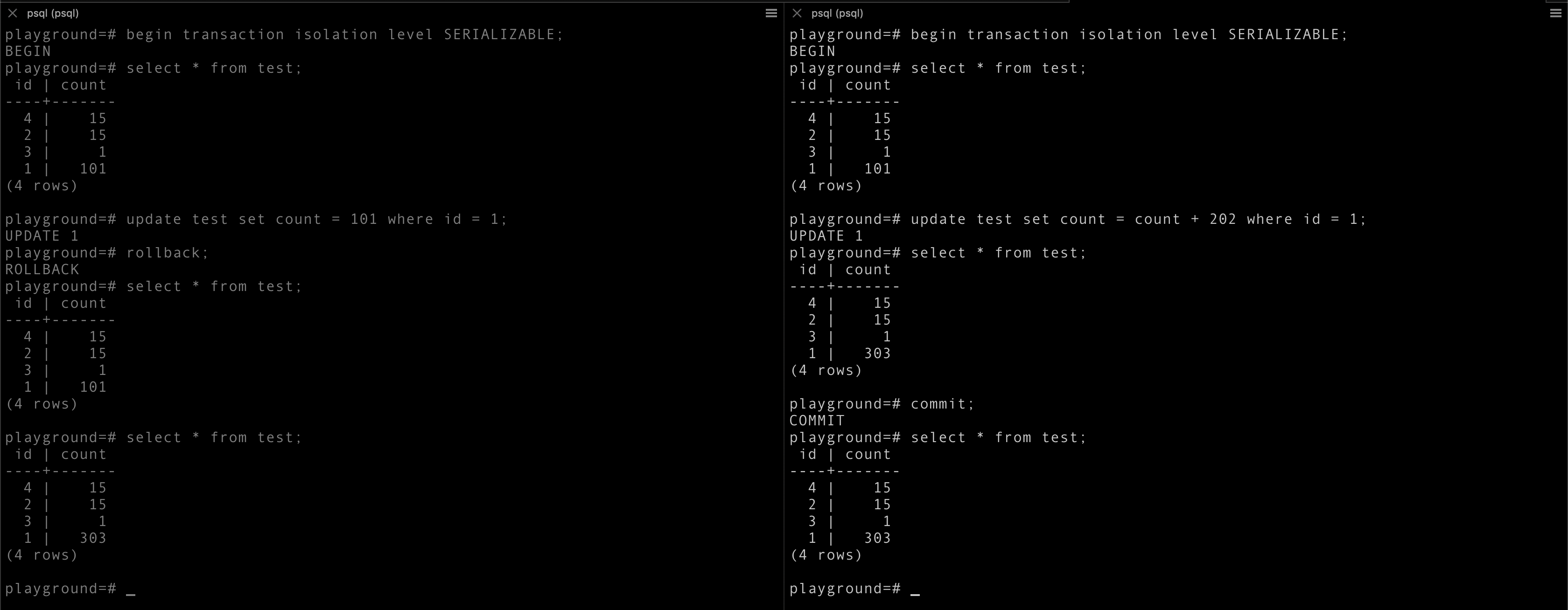

- But if we rollback left-hand side transaction, then the right one is able to commit.

In the above two cases, we were trying to update the same tuple. Now let’s try to update different tuples in different Serializable transactions.

Although we were able to update different tuples in two different transactions but were not able to commit both the transactions.

Conclusion: as the name implies, only one transaction at a time. The parallel transaction will not be able to commit.

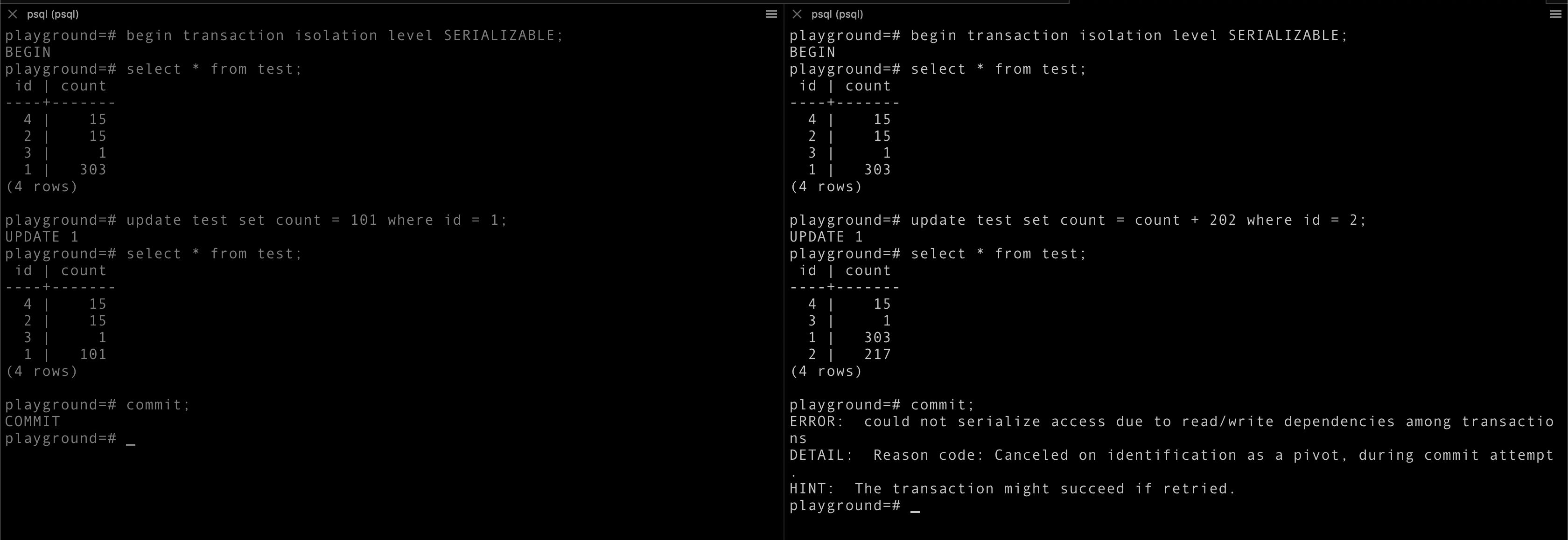

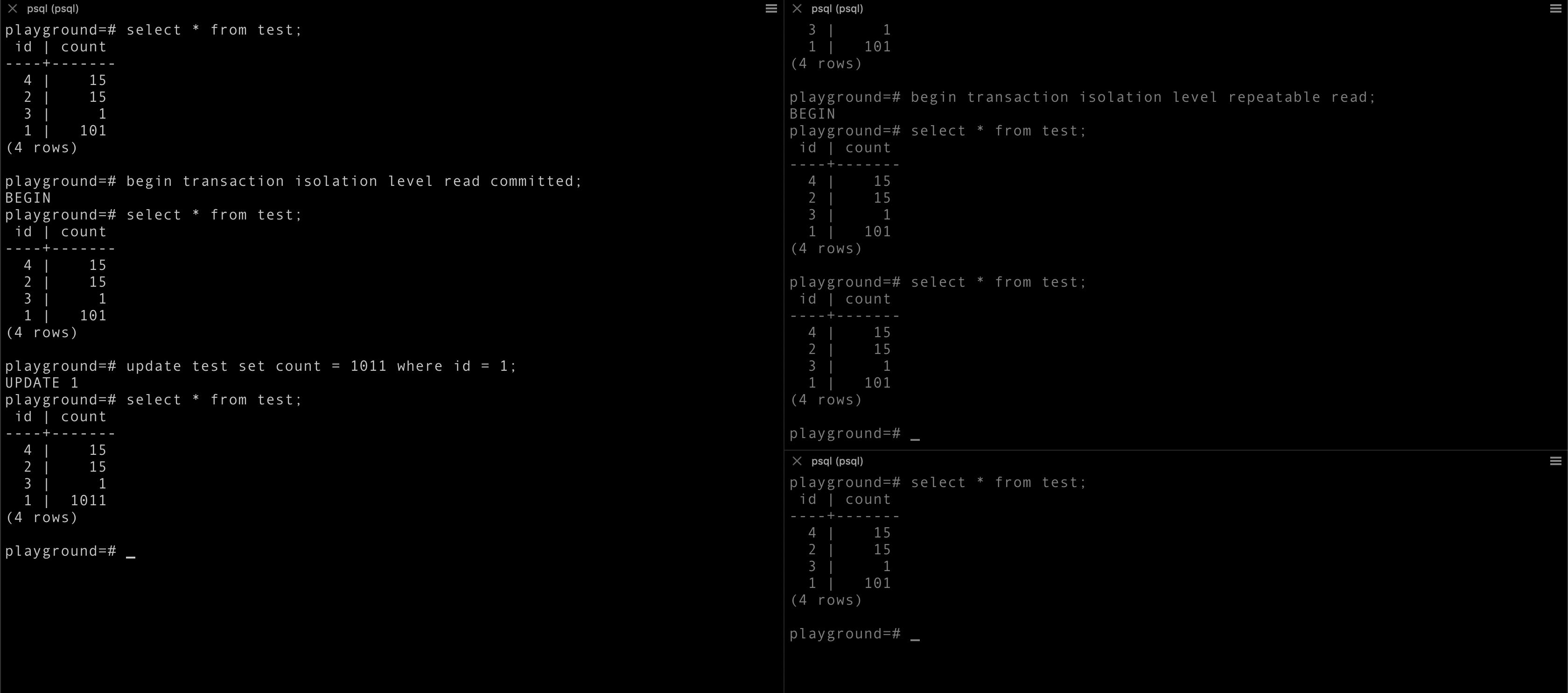

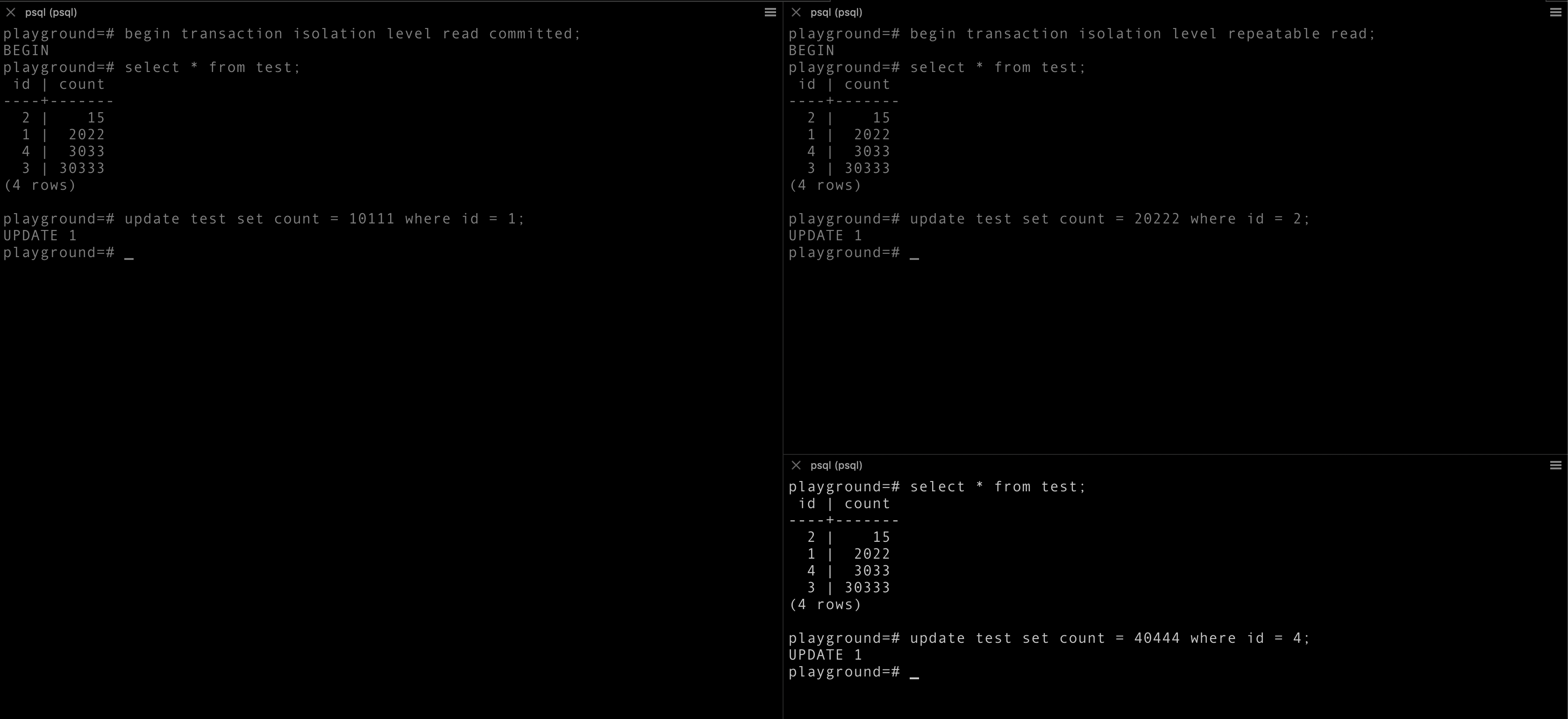

Read committed transaction

Read Committed is a default isolation level in PostgreSQL. This gives assurance that you will never read any uncommitted change from another transaction.

Let’s take an example

In both the above cases, changes made in a transaction are only visible within the transaction until they are committed. Thus no chance of dirty read.

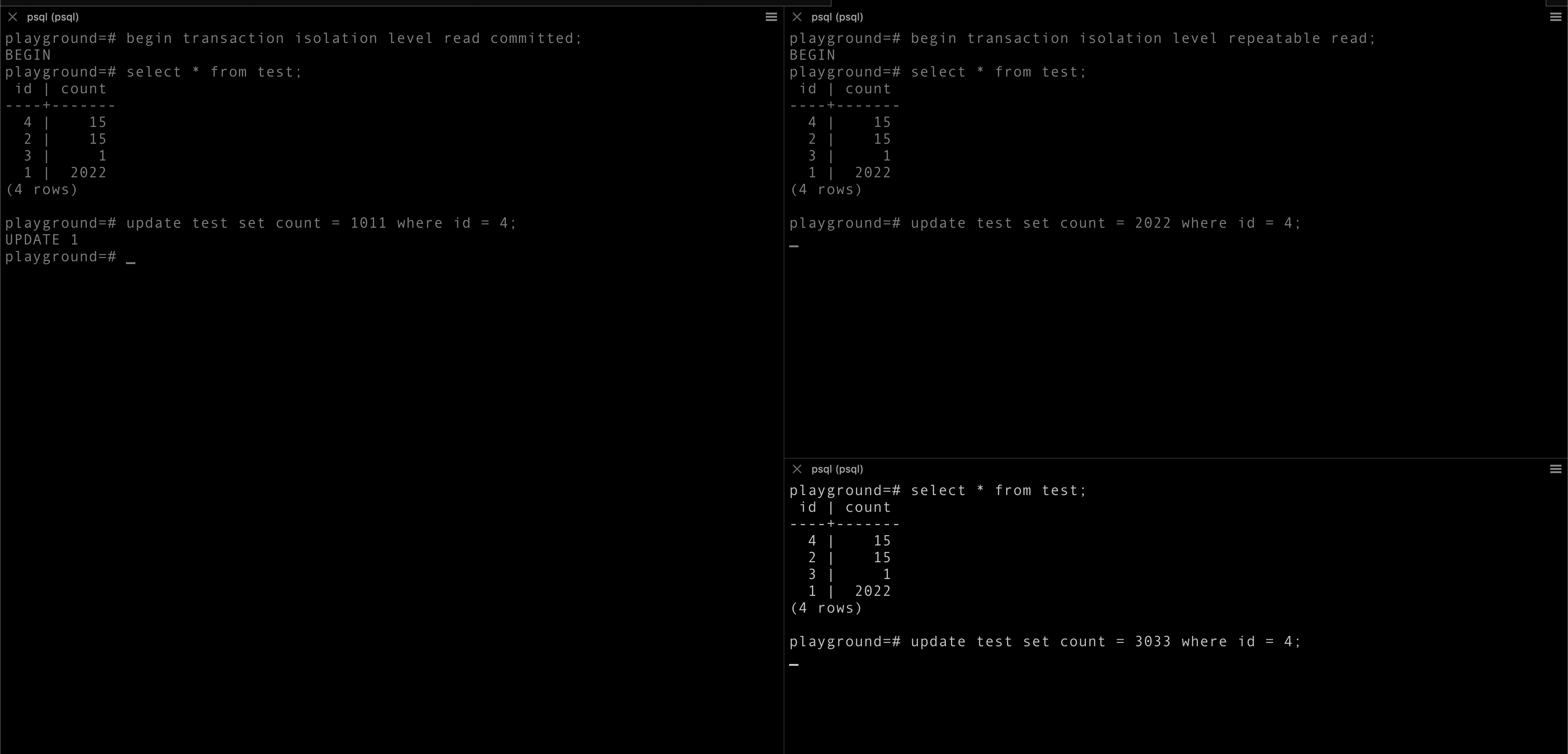

Now let’s try to update the same tuple in two different transactions.

Have you observed that all the later updates are waiting for the first one to complete, either commit or rollback.

- Let’s say we commit the first transaction:

The second transaction failed with an error:

ERROR: could not serialize access due to concurrent update

but the updated value id 3033 that means query without any transaction got excecuted and had overridden the first transaction update.

In such cases using delta update will help, just tweak your query to:

update test set count = count + 3033 where id = 4;

So that, changes are not overridden.

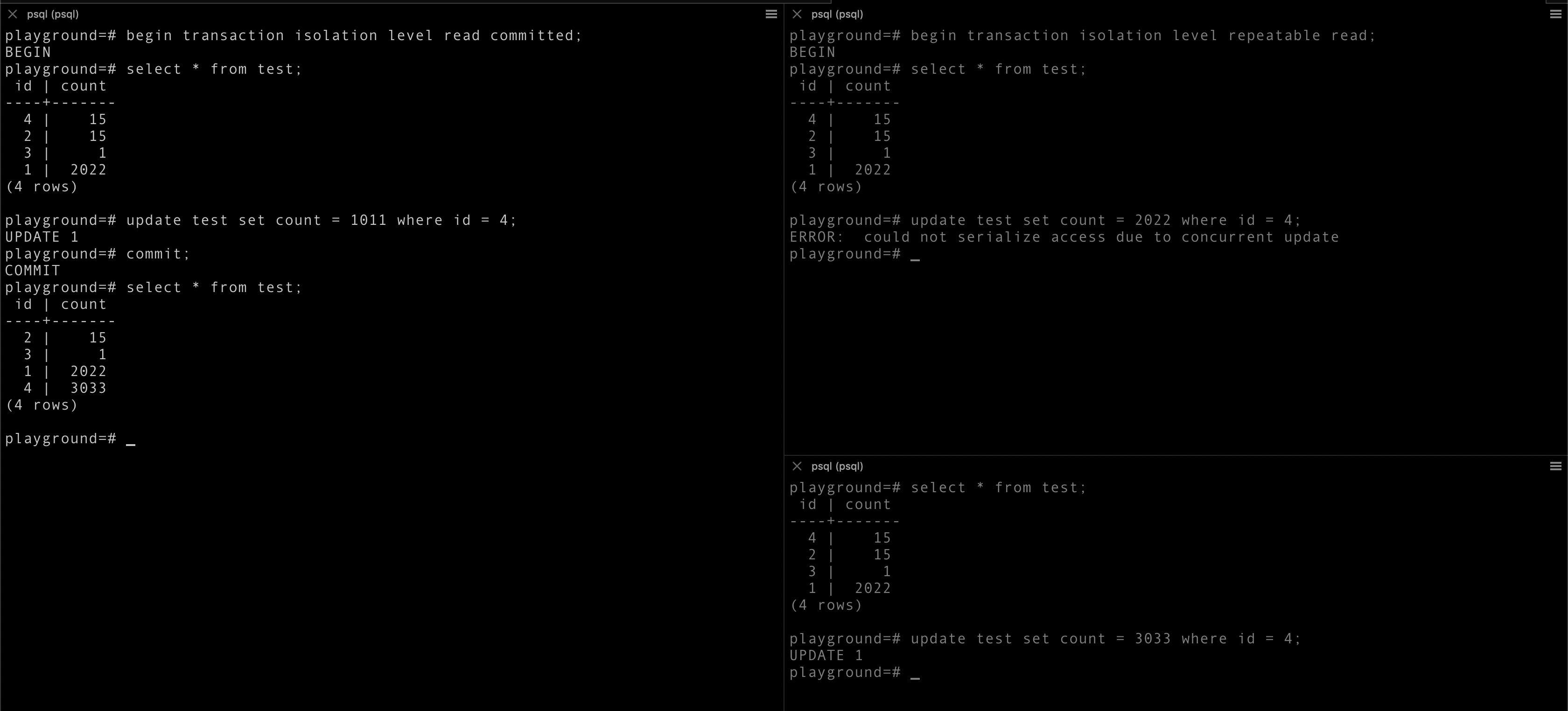

- Now let’s see what will happens if we rollback the first transaction:

After rolling back the first transaction, the next one i.e second one got executed. Still, the 3rd one is pending. As it is without any transaction, after completion (either commit or rollback) of the second transaction it will anyhow execute.

Note: Here quires are executed in first-in, first-out (FIFO) fashion

Not let’s try to update different tuples in different transactions.

Oh, all updates are successful.

Conclusion:

- It takes a lock on a tuple, so that no other transaction will be able to update on it.

- Changes done in a transaction are only visible within the transaction until committed.

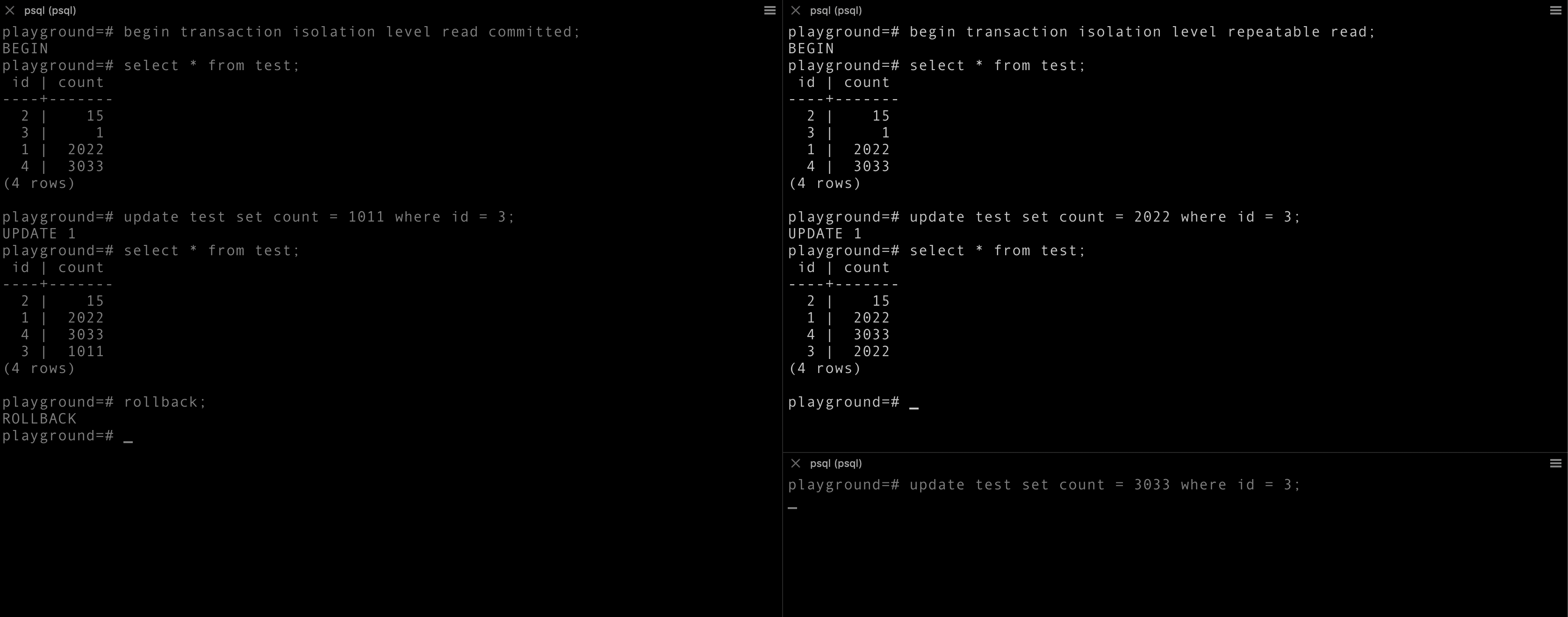

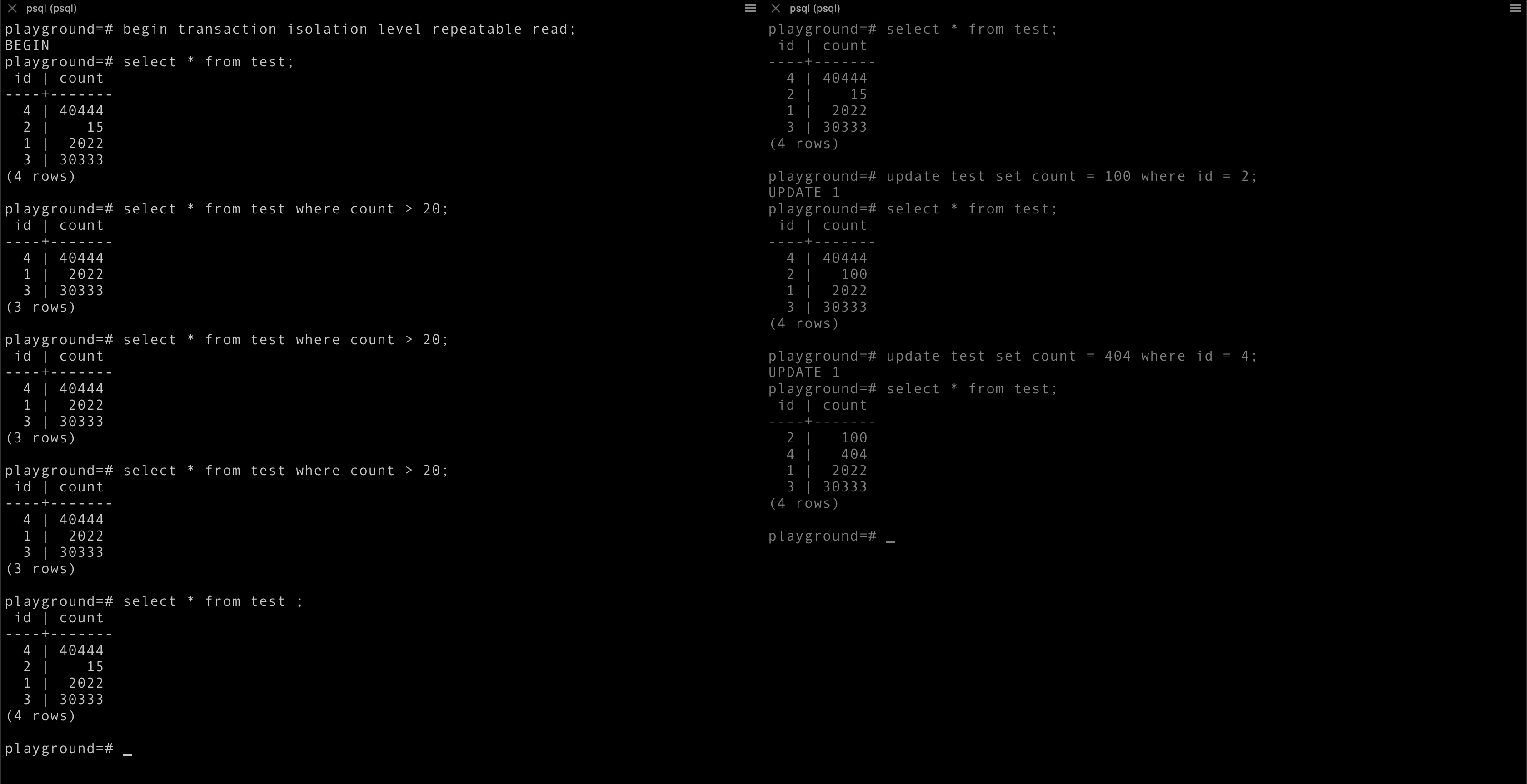

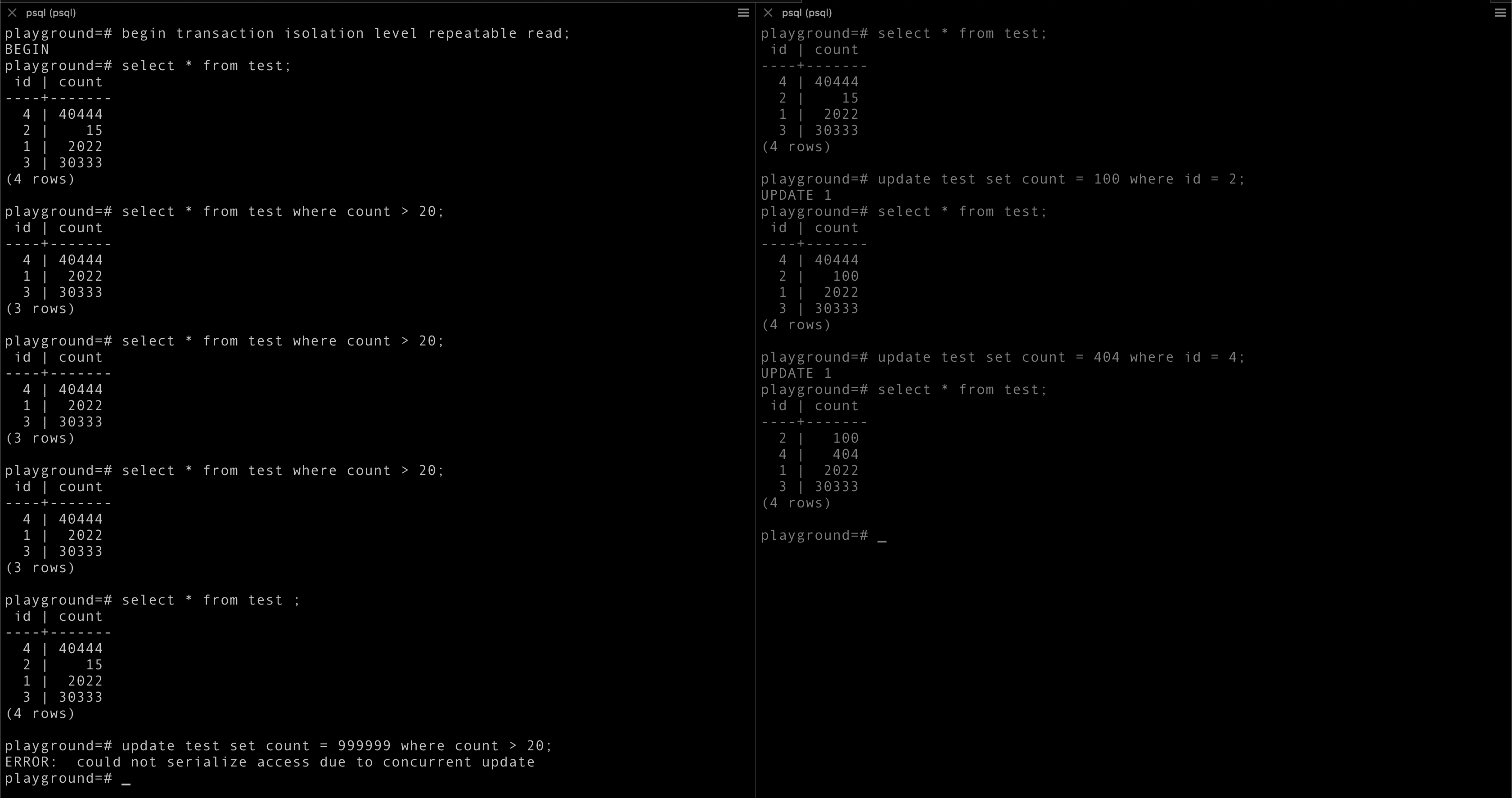

Repeatable read transaction

It is more strict then Read committed. In addition to all that Read committed offers, Repeatable read also offers you guarantee what, whatever you have read will not change for that transaction.

As you can see in the above example, the output of select quires are constant even after data is changed.

But when you try to update on outdated data, then it throws an error

ERROR: could not serialize access due to concurrent update

Conclusion:

- Whatever is read, will always be same within the transaction scope.

- But update operations will not work if changes are made on top of it.

This was all about handling transactions in postgresql. Thanks for reading. Hoping to write more blogs on Hands on series.

Note: In this blog concurrency and parallelism are used interchangeably, though both are different. The aim is just to differentiate it from sequential.

Huge thanks to @ronakjc for pairing with me on this!